By Armando

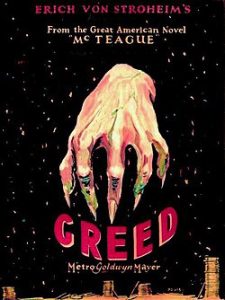

A century after its release, Greed (1924) still feels modern. The nearly four-hour reconstructed version, created in 1999 by Turner Classic Movies, restores Erich von Stroheim’s lost footage by combining the surviving reels with hundreds of still photographs after the studio famously cut and destroyed most of his original film.

A century after its release, Greed (1924) still feels modern. The nearly four-hour reconstructed version, created in 1999 by Turner Classic Movies, restores Erich von Stroheim’s lost footage by combining the surviving reels with hundreds of still photographs after the studio famously cut and destroyed most of his original film.

For a movie made a hundred years ago, it feels current, not in style or pacing, but in spirit. Its themes, the rawness of its characters, and the way it exposes human nature feel as if they belong to right now. Watching it is like holding up a mirror and realizing we haven’t changed much at all.

Reconstructing a Ghost

In this version, some parts unfold in motion, others through still photographs of scenes lost when the studio destroyed Stroheim’s original cut. The reconstruction used these images to bridge the missing footage and preserve the story’s rhythm. Watching this mix creates a ghost-like experience, one that makes you imagine and fill in the missing pieces. In that act of reconstruction, the film becomes a collaboration between the dead and the living, between Stroheim’s impossible ambition and our modern imagination.

Stroheim was a Viennese-born immigrant who came to America looking for work and eventually found his way into films. His reputation at the time was controversial, not for scandal, but for insisting on realism in his films. Shot in real locations, the film was famously cut down from an eight-hour epic to just over two. What survives today is part motion and part stills.

What Remains of Greed

The story follows McTeague, a San Francisco dentist whose simple life starts to break apart. He marries Trina, who wins a lottery, and something in both of them shifts. What begins as affection slowly turns into control, fear, and frustration. Stroheim isn’t dressing anything up here; the film leans into the sweat, the grime, and the small, painful choices people make.

As things get worse, McTeague loses his sense of direction, and Trina becomes fixated on protecting the money she won. Marcus, McTeague’s friend and Trina’s former suitor, never really gets over stepping aside. His frustration turns into spite when he reports McTeague for practicing without a license, and from there the story moves in a straight line toward its ending. Stroheim shows these people without blaming them, but without softening anything either.

The film ends in Death Valley, with two men chained together, fighting over gold in the heat. It’s a harsh finish, but it fits the story. What stays with you isn’t the shock of the moment, but how familiar the emotions are, the pride, the anger, the way people hold onto things even when it hurts them.

Made in 1924, Greed could just as easily be about now. The same ambitions, the same moral exhaustion, the same fascination with wealth and ruin. Stroheim’s realism still feels radical a century later. The four-hour reconstruction endures as proof that even when art is damaged, it can outlive everything else. The fragments, the lost footage, the stills, the ghosts, all feel fitting for a film about human appetite. We never get the whole thing, just enough to want more.

Where to Find Greed

Various DVD editions of the shorter, 140-minute theatrical version have circulated since the late 2000s, often from European distributors like Llamentol. The more complete four-hour reconstruction, however, remains most accessible through digital platforms like Amazon and Tubi, a fitting afterlife for a film that refused to disappear, even after being cut, chopped, and destroyed.